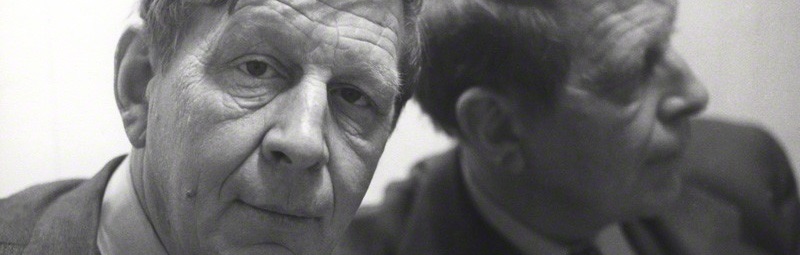

奥登 [W. H. Auden] 百年诞辰

21日是奥登百年诞辰日。

Auden, W(ystan) H(ugh) (1907–73), was born on 21 February 1907 into a provincial English world still Tennysonian in outlook. He was the third son of a gentle, cultivated family doctor and a domineering former nurse who had once wanted to go to Africa as a missionary. Auden was by nature a versatile, polymorphous writer, one who felt that, amongst other things, poetry was ‘a game of knowledge’. The odd geometry of his parents’ marriage seems to have added an intellectual openness and restlessness, even as it left him personally extremely anxious. He boarded at Gresham’s School in Norfolk, then in 1925 went up to Christ Church, Oxford, where he soon switched from reading biology to English.

For a collected edition made late in his career, Auden divided his poetry into broad phases; each constituted, he felt, a ‘chapter’. The first stretches from 1927 until the end of 1932, and in it Auden emerges from the sacred ground of English Romanticism, the Lake District. The landscape of these guarded, archaic-sounding poems is the same as Wordsworth’s, though in Auden the area is desolate and the solitary is numbed by feelings of intense isolation and disappointment. Even the shared resources of English are denied: conjunctions and pronouns have flaked away, leaving a language of glittering, compacted hardness.

A pamphlet, Poems, was cranked out on a hand-press by his friend Stephen Spender in 1928. The same year Auden left Oxford and spent the next nine months in Germany (mainly Berlin), writing, reading widely in psychology, and brothel-crawling. At a moment when Europe’s foundations were starting to shudder, he also became concerned about political issues. In September 1930, a few months after Auden had returned to England, T. S. Eliot at Faber and Faber published Auden’s first full-length book, again austerely called Poems (London, 1930). Meanwhile, Auden had gone off to teach at a seedy Scottish prep-school.

In Poems (1930) there is a dark, autistic vein of love poetry; there is also a kind of admonitory satire, castigating Britain’s spiritual torpor. His next book, The Orators (London, 1932), is the culmination of both these tendencies and it reads like a surrealist explosion of language. There are hints of a narrative involving a failed insurrection against the governing class, but the real subject of The Orators is its own bristling verbal energy.

Despite the obscurity of his early work, Auden was hailed by critics as the leader of a group of young, left-wing, writers that included Louis MacNeice, Spender, and C. Day Lewis. Backed by Eliot, and fuelled by a growing literary confidence, Auden seems to have felt for a while that he could have a role to play in the country’s renewal. This belief soon evaporated, and by the end of the decade he was to feel trapped by his sense of responsibility. None the less, the revolutionary ‘movement’ was an important means of self-definition for these poets as they were crawling out of the shadow of Yeats and Eliot. It also gave Auden a clearly defined audience to write for and a reason to try and forge an accessible public style.

He soon came to see The Orators as a botched effort, and his work, which shows a strong evolutionary urge, began to move forward. In the autumn of 1932 he started teaching at the Downs School in Herefordshire. In that mellow world his poetry opened like a bud, becoming more expansive and much richer in surface detail. This is the start of the second ‘chapter’, the phase when Auden, drawing on Marx and Freud, was able to make a brilliant stream of connections between individual guilts and pleasures and the crisis that seemed to be eating away at European civilization. Simultaneously, his interest in the possibilities of verse-forms burst out in a profusion of beautifully adroit sonnets, sestinas, and ballads.

Auden was a homosexual, but in 1935 he married Thomas Mann’s daughter, Erika, a fugitive from Nazi persecution, in order to get her an English passport. The same year he left the Downs. In search of a wider field of vision he joined a documentary film company, where he worked briefly and unhappily. For six years after that he was a free-lance writer. A second collection of lyrics, Look, Stranger! (London, 1936)—the American edition is On This Island (New York, 1937)—extended his reputation.

So did his plays. Auden had composed a long charade, ‘Paid On Both Sides’ (1928), and a polemical ‘masque’, The Dance of Death (London, 1933). In the later Thirties he and Christopher Isherwood turned out a string of dramas: The Dog Beneath the Skin (London and New York, 1935), The Ascent of F6 (London, 1936; New York, 1937), and On the Frontier (London, 1938; New York, 1939). Although none of the plays is a fully integrated work, they contain flashes of great poetry. The choruses in The Dog Beneath the Skin offer huge panoramas of English life, and F6 contains an allegory of Auden’s early fantasy of himself as a healer and redeemer of society. He later said it was while working on the play that he realized that, for the sake of his artistic growth, he would have to leave England.

Auden’s pre-war years were a period of fertility in many media and of almost continuous wandering. In 1936 he went with MacNeice to Iceland (where he liked to believe his ancestors had come from), a trip that resulted in their Letters from Iceland (London and New York, 1937). The volume contains Auden’s masterpiece of autobiographical light verse, ‘Letter to Lord Byron’. Then, in January 1937, he went to observe the Spanish Civil War. Auden was never a member of the Communist Party, and he seems to have been shunted aside by the party bosses in Spain. Immediately after he returned, though, he wrote his most famous call to action, ‘Spain’, a poem full of local brilliance but one that cannot now be separated from knowledge of the Civil War’s tragically convoluted history. Auden hardly ever spoke about his experiences in Barcelona, but in the wake of the visit his poems darkened; many from the later Thirties are bleakly pessimistic, shielding themselves from the historical turmoil behind layers of stylization and irony. In early 1938, after he had hurriedly assembled his Oxford Book of Light Verse (London, 1938), Auden went abroad again, this time with Isherwood. They travelled to China to write about the Sino-Japanese War. Their book, Journey to a War (London and New York, 1939) became a parable about the difficulty of politically engaged writing: as Isherwood recounts it, they could never find any clearly drawn lines of battle in China. The problem is developed in the volume’s sonnet sequence ‘In Time of War’, which finds the war going on everywhere, all the time. The sonnets show an important broadening of Auden’s moral imagination, and throughout, Christian symbolism begins to bubble to the surface. On their voyage to England in mid-1938 Auden and Isherwood stopped off in New York. In January 1939 they went back there.

Going to America was another turning-point, and Auden began purging himself of a rhetoric that he felt had now been exhausted. The next phase of his career, initiated by a series of elegies and psychological portraits, is a period of much more intimate writing, concerned above all with subjectivity and loneliness. He had fallen in love with a younger American writer, Chester Kallman, and his happiness seems to have released a flood of other feelings, including what were only half-suppressed religious impulses. Another Time (New York and London, 1940) contains some of his best work, though, as the title indicates, the poems already seemed to him to belong in a vanished era. The book includes ‘September 1, 1939’, a lyric written the weekend war was declared, which tries to come to terms with the failure of the ‘clever hopes’ of a ‘low dishonest decade’ for social and personal renewal, and attempts a new, modestly heroic, role for the writer. Auden later came to dislike the sanctimoniousness of the piece.

The suggestions of religious and poetic conversion were strengthened in The Double Man (New York, 1941; published in London the same year under the title New Year Letter). Again admitting the failure of the utopian hopes of the Thirties, the volume’s main element, a long neo-Augustan verse epistle, is a dissection of man’s spiritual predicament and of the dualism in European secular thought which Auden believed had ultimately led to the catastrophe of war. It ends with a petition for aid from a mysterious—though still unnamed—power. Around October 1940, just after he finished the book, Auden began going to church.

Although he remained a Christian for the rest of his life, Auden never became pious or dogmatic, at least in his poems. In fact his faith seems to have increased his intellectual appetite. By inclination his mind was speculative, synthesizing, and eclectic—he was probably the only poet from the earlier half of the century well acquainted with the most advanced thought of the day—and Christianity allowed him to order this vast store of knowledge from philosophy, history, and theology into a harmonious and poetic world-view.

In the next few years he produced three more long poems. Each addresses the situation created by the ‘crisis’ of the war and of his conversion to Christianity, and each deals with its implications for his art. It is a retrenchment in the form of an enormous, almost forbidding, flowering: Auden’s developing artistry feeds off his complex feelings about literature, and particularly about his own early writing. Two of these poems, ‘For the Time Being’, a Christmas Oratorio dedicated to his mother who had died in 1941, and ‘The Sea and the Mirror’, a verse ‘commentary’ on The Tempest that Auden described as his ‘Ars Poetica’, were published together in For the Time Being (New York, 1944; London, 1945). His final long poem is The Age of Anxiety (New York, 1947; London, 1948). This ornate, rather Joycean work, which won the 1948 Pulitzer Prize, is an interior portrait of the average twentieth-century city-dweller, cast in the form of a meeting between four New Yorkers in a bar on All Souls’ Night, 1944.

Between 1939 and early 1947 much of his time was taken up with work on these long poems and earning a living as a university lecturer. In 1945, though, he spent a few months in Germany as an observer with the US Air Force’s ‘Strategic Bombing Survey’, studying the effects of aerial bombardment. Amongst the ruins of Darmstadt and Munich his interest in rebuilding cities took on renewed urgency, and some of his most ambitious works of the post-war years open out into an investigation of how to unify the contemporary world. The most important in this respect are the poem ‘Memorial for the City’ (1949), and a series of anti-Romantic lectures, The Enchafèd Flood (New York, 1950; London, 1951).

In 1946 Auden became a U.S. citizen. The following year was one of artistic uncertainty, a time when he was again casting around for a new literary direction. Once more a fresh ‘chapter’ began with a change of air. From 1948 until 1957 Auden summered—and wrote most of his poetry—on Ischia, an island in the Bay of Naples. This period, during which Auden became the first truly rootless, international poet since Byron, was inaugurated by the elegiac syllabics of ‘In Praise of Limestone’. The poem appeared in the transitional Nones (New York, 1951; London, 1952). The Mediterranean breathed a restrained, ‘classical’ feeling into Auden’s work, and renewed his interest in the natural world and in the great movements of human history. The poems are more relaxed, but there is no slackening of artistic authority: his writing is both colloquial and gracefully elevated.

Auden believed that every poem should pose a new technical challenge for the poet. Thus, formal precision is balanced in the Fifties by a great deal of formal experimentation. The main thematic preoccupation is with the humanist task of defining Man through his relations with the world around him, and this culminates in a pair of major sequences from mid-decade: ‘Bucolics’ and ‘Horae Canonicae’. Both were published in The Shield of Achilles (New York and London, 1955), along with that book’s title poem, a meditation on the West’s culture of violence. The final pieces from the period were gathered into Homage to Clio (New York and London, 1960).

As his verse became more conversational, Auden found an outlet for his love of the grand style by writing opera libretti. (He had already worked on an operetta, Paul Bunyan, with Benjamin Britten in 1939–1941.) He and Kallman now produced the words for Stravinsky’s The Rake’s Progress (1951). Later they collaborated on Elegy for Young Lovers (1961) and The Bassarids (1966), both by Hans Werner Henze, and Love’s Labour’s Lost (1973) by Nicolas Nabokov.

Auden’s activities were not confined to poetry and opera, though. He also produced a torrent of critical prose and, with Norman Holmes Pearson, edited a five-volume anthology of verse, Poets of the English Language (New York, 1950; London, 1952). From 1956 to 1961 he was Professor of Poetry at Oxford, countering the authority of his lectures in the Sheldonian with a stream of baroque occasional verses and academic clerihews.

In 1958 he and Kallman moved again, this time to a summer cottage outside Vienna. Increasingly Auden’s poetry came under the influence of Herbert and Dryden, becoming dryer and more sober, though he set even the most apparently parochial of his poems in the sweep of long historical vistas. In fact, Auden was now beginning to produce a subtle, highly crafted poetry of old age, crankier, but also much more topical and political than it had been for several decades. He continued to seek out new formal challenges as well, and his long, chatty meditations are interspersed by showers of brilliantly sharp haiku diary-jottings. Both sides of this Goethean persona are represented in About the House (New York, 1965; London, 1966), which contains another major sequence, a poem for every room in his home, except—their relations continued to be complicated—Kallman’s bedroom.

Auden’s final books, City Without Walls (London, 1969; New York, 1970), Epistle to a Godson (New York and London, 1972), and the posthumous Thank You, Fog (London and New York, 1974) are the completion of the curve. Each of these books contains important poems: wry, ego-less musings in which extinction—feared, witnessed, and, occasionally, inflicted—is a frequent subject. Auden maintained that poets died once they had finished their historically appointed task. He spent the summer of 1973 in Austria and had planned to fly back to Oxford, where he now spent his winters. However, on 28 September 1973, in the middle of his last night in Vienna, he suffered a fatal heart-attack.

Since his death Auden’s polemical aura, whether in its early political or in its later High-Churchy form, has faded. He now seems an extraordinarily comprehensive and various writer; not one voice, but many. He was a master of the sparkling detail who also loved the vast, inhuman overviews of geography and history, a poet of great technical finesse who was ambivalent about the worth of literature, the century’s wittiest public versifier who could also sound the note of someone speaking out into an unpeopled silence. Only a major poet could have mingled and brought to perfection so many different styles, and only a great one could have been so ready to throw away his successes and move on.

The bulk of his work is part of its meaning, too. In historical terms, his importance lies in his reaction against Modernism’s tortured sense of stasis and restriction. Auden is a self-effacing poet: the nearest he got to an autobiography was A Certain World (New York and London, 1970), a vast collection of his favourite texts from other writers. Looked at from one point of view, this distaste for personal revelations and visionary extremity can be traced to the accidents of his psychological make-up. Looked at from another, though, his encyclopedic intellectual scope, his polyglot linguistic inclusiveness, and his insistence that all forms and subjects are still available to the contemporary poet, look like the dynamic of poetry working itself out through him. Auden is a powerful precursor figure for later poets, and his voice reverberates in writing as different as Lowell’s churning sonnets and Ashbery’s cool, loose webs.

The bibliographical situation is tangled, and no one book can represent all the important facets of Auden’s career. The bedrock is the Collected Poems (2nd edn., New York and London, 1991). However, when Auden was trying to discover what sort of poems he wanted to write next, he often looked back sourly on earlier work and even cut out several key poems, notably ‘Spain’ and ‘September 1, 1939’. This means that the Collected Poems must be supplemented by two anthologies. The English Auden: Poems, Essays and Dramatic Writings 1927–1939 (London, 1977; New York, 1978) provides a much broader picture of the first decade or so, and includes The Orators. For the original version of ‘Spain’, the reader needs the Selected Poems (New York and London, 1979). All three are edited by Auden’s literary executor, Edward Mendelson. A multi-volume, historically oriented edition, The Complete Works of W. H. Auden, also under Mendelson’s editorship, is under way. To date, a volume of the dramas written with Isherwood, Plays and Other Dramatic Writings 1929–1938 (Princeton, NJ, 1988; London, 1989), and a volume of the libretti composed with Kallman, Libretti (Princeton, NJ, and London, 1993) have appeared. In addition to The Enchafèd Flood (see above), there are three collections of fairly late prose: The Dyer’s Hand (New York, 1962; London, 1963), based on Auden’s lectures as Professor of Poetry at Oxford; Secondary Worlds (London, 1968; New York, 1969), the 1967 T. S. Eliot Memorial Lectures; and Forewords and Afterwords (New York and London, 1973). However, a huge quantity of valuable material is still buried in the back numbers of little magazines. For guidance, consult W. H. Auden: A Bibliography 1924–1969, by B. C. Bloomfield and Edward Mendelson (2nd edn., Charlottesville, Va., 1972). Information on work from the final few years of Auden’s life and on discoveries made since his death can be found in Mendelson’s ‘W. H. Auden: A Bibliographical Supplement’, in Katherine Bucknell and Nicholas Jenkins (eds.), W. H. Auden: ‘The Map of All My Youth’ (Oxford, 1990). The best account of Auden’s life is Humphrey Carpenter’s W. H. Auden: A Biography (London and Boston, 1981); Alan Ansen’s The Table Talk of W. H. Auden (New York, 1990; London, 1991) gives a good impression of his witty, playful intelligence. Critical works include A Reader’s Guide to W. H. Auden, by John Fuller (London, 1970), The Auden Generation, by Samuel Hynes (London, 1976; New York, 1977), Early Auden, by Edward Mendelson (New York and London, 1981), and W. H. Auden, by Stan Smith (Oxford, 1985). Auden left instructions that after his death his friends should burn all letters from him. In fact not much seems to have been destroyed, but until publication of the Complete Works is finished no edition of his correspondence will appear.

Author: Nicholas Jenkins.

From The Oxford Companion to Twentieth-Century Poetry in English.