词与物是分离的;人们常常为“词”而激动。——“奥运圣火”到北京的活动又让我想起了这个话题。昨天下午,“圣火”经过清华园的时候,我恰好也路过那里,于是就见怪不怪地再一次亲历了激动的人群、旗帜和欢呼。

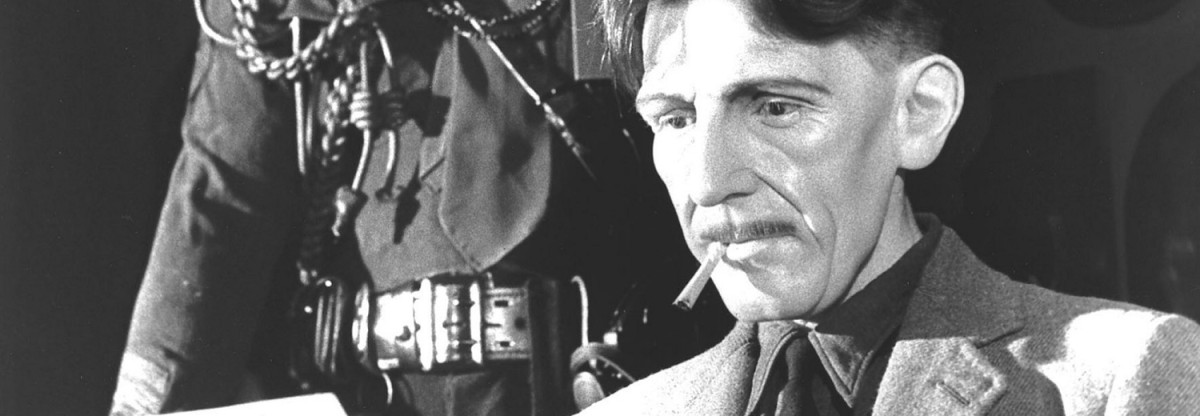

一九七〇年代出生的这代人,凡是学过英语的,大多都会念过《新概念英语》。《新概念英语》中有一篇 George Orwell 的(半个多世纪以前的)美文:“The Sporting Spirit”,我猜想有不少学过它的人未必真的记住了,或者至少没有 taking it seriously。借着首次光临华夏的“奥运圣火”的光芒,再复习一下这篇英语课文,大约是不无裨益的:

I am always amazed when I hear people saying that sport creates goodwill between the nations, and that if only the common peoples of the world could meet one another at football or cricket, they would have no inclination to meet on the battlefield. Even if one didn’t know from concrete examples (the 1936 Olympic Games, for instance) that international sporting contests lead to orgies of hatred, one could deduce it from general principles.

Nearly all the sports practised nowadays are competitive. You play to win, and the game has little meaning unless you do your utmost to win. On the village green, where you pick up sides and no feeling of local patriotism is involved, it is possible to play simply for the fun and exercise: but as soon as the question of prestige arises, as soon as you feel that you and some larger unit will be disgraced if you lose, the most savage combative instincts are aroused. Anyone who has played even in a school football match knows this. At the international level sport is frankly mimic warfare. But the significant thing is not the behaviour of the players but the attitude of the spectators; and, behind the spectators, of the nations who work themselves into furies over these absurd contests, and seriously believe–at any rate for short periods–that running, jumping and kicking a ball are tests of national virtue.

苏力:《走不出的风景:大学里的致辞,以及修辞》,北京大学出版社2011年。ISBN: 9787301089279.

苏力:《走不出的风景:大学里的致辞,以及修辞》,北京大学出版社2011年。ISBN: 9787301089279.